When I see something ignorant, robotic, and false being held up as brilliant, innovative, and true, I think of how good my life must be. I tell myself there will always be stupidity and hypocrisy in the world, especially in writing and publishing. I remind myself that it’s better to feel compassion for people caught up in mistakes than criticize their blindness. And I admit that I’m fallible.

Yet there are moments when human nature undercuts my better judgment and I feel willing to kick the kitten that just vomited something on my doorstep. I’m not proud of such feelings. But no matter how much I meditate, no matter how much Thich Nhat Hanh I read, there’s a cruel, stony part of me that just doesn’t care. It’s a hard world, Fluffy. Get off my porch.

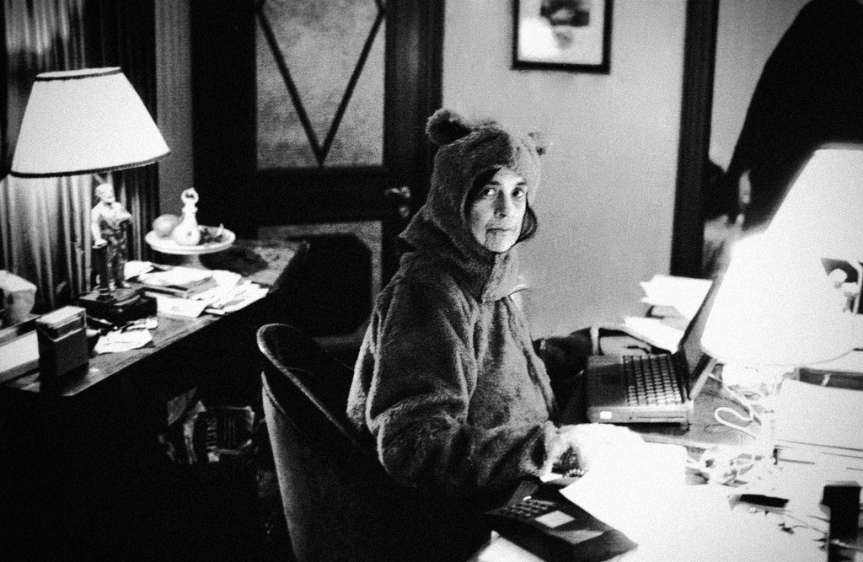

I quit smoking 20 years ago. Everyday some part of me still wants a cigarette, which is probably why the characters in my short stories smoke. At least someone still gets to enjoy it. But I’ve had some great writing insights over cigarettes and coffee—more, I’m inclined to think, than I do now, even if my caffeine consumption has grown to replace the nicotine. I have clean lungs and a rapid heartbeat. I’m wired but not as wise.

This might be the root of my intolerance. Some writers really need to start drinking again. They’re not able to produce unless they do. Maybe if I went out and bought a carton of Camel Lights, I’d look at many of the insipid things currently promoted as quality writing and smile along with the alcoholic cigarette ghost fume of Jack Kerouac, who once declared in a letter: “I don’t know; I don’t care; and it doesn’t make any difference.” That’s it. Light up. Nothing matters.

Long ago, at the University of Montana, I found myself on a smoke break during a one-day-a-week, four-hour creative nonfiction workshop that nobody wanted to take. There were five or six other MFA-program degenerates in the class. We couldn’t get the workshops and literature sections we needed due to a writing professor having a midlife meltdown the previous spring (which included loudly and publicly criticizing his terminally ill wife, sleeping with his students, physically threatening other faculty in the hall, and declaring that he thought we were all imbeciles). Of course, he had tenure. So he went on leave. Now it was almost Christmas. And we’d signed up for electives to kill time and keep our tuition waivers flowing until the search committee hired a temporary replacement. Morale was low.

When English studies people fall, they fall hard. This is known. We were all trying to keep it together. Hence multiple smoke breaks behind the five-story, brutalist classroom building in the dark, snow up to our knees. There was, I should admit, a deluge of alcohol being consumed that semester. Cocaine was too ambitious and, honestly, too expensive. But whiskey in Montana? Shit, it came out of the water fountains.

Andrea was my smoke-break buddy. She’d go out the back of the building and lean against the parking lot hydrant. I always ran into it because it was covered in snow. Paying attention to things like hidden fire hydrants seemed to require a volume of positive life-affirming energy I just didn’t have. So I barked my shins on it regularly. But that was Andrea’s bitter smoking spot. Out in the desolate lot in her enormous down jacket, she was a shadow and a tiny ember. I’d walk over and stand next to her. We wouldn’t talk much. The protagonist in every one of Andrea’s stories was Taylor Swift. Once you know that, there isn’t much left to say.

She spent a lot of time obsessing over Lauren, a fellow student and the darling of the department, whose dad was a media executive and had paved his daughter’s way to a book deal and literary fame well before she came to grad school. This was the ostensible origin of Andrea’s bitterness. No one suggested that, apart from having family in publishing, success might have been more forthcoming if Andrea hadn’t made every story about Taylor Swift. But nobody knew anything. If her collection of stories had gotten published alongside Lauren’s novel and Andrea had gone on a big book tour, everyone, especially the faculty, would have seen it as a sign of the new literary age, the new 20 under 30. But as it was, Lauren remained the “it girl.”

Sometimes we talked about Lauren, who no one ever saw in class because she was skiing in Vail or visiting friends in Spain or doing a book tour or attending a gallery opening. We had to sit in a bright classroom that smelled like hospital disinfectant. We had to read each other’s boring attempts at fiction-adjacent prose and make helpful comments. And when we weren’t doing that, we had to talk about things like Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, The Year of Magical Thinking, and the rhetoric of Vietnam war propaganda. Meanwhile, Lauren was living the life.

Maybe Andrea forgot what I remembered: I was here to talk about those things, not to lead the life. This was not real life. This was a sub-dimension, a demimonde, an absurd mirror world where we could obsess about each other, be jealous and competitive over silly things, and wind up reading texts we never wanted to read in classes we never wanted to take. A small part of me knew it was glorious and someday I’d look back at it like a weird fairyland where I had seemingly unlimited hours to write and think and talk about art. And maybe that radiated outward because I always seemed to cheer Andrea up on our smoke breaks, even if we didn’t talk all that much.

But the smoke break I remember so vividly was the one where Andrea pulled out a hardcover of Lauren’s recently published novel and handed it to me without comment. I’m not going to name it because Lauren and her novel are real and the book is still in print. I’d read parts of it in previous workshops and I knew, just as Andrea knew, that it was garbage.

Lauren had everything necessary for meteoric success and it didn’t hurt that she was charming, smart, cultured, and gorgeous. But she couldn’t write. Years later, I’d hear that her prestigious publishing house performed a very invasive round of edits to the point where subsequent drafts were almost ghostwritten (maybe ghost rewritten). But I chalked that up to jealous post-program rumors. Now, I’m not so sure.

I remember angling the book so I could see it in the light from classrooms, snowflakes landing on the pages. I remember Andrea blowing a funnel of smoke at my face, as if to say, “See?” or maybe “Take that, you cheerful moron.” Take that. Take it and like it.

I handed the book back, and said, “Good for Lauren.”

And I remember Andrea shaking her head, smiling at the corners of her mouth, taking long drags, saying, “Yeah. Good for Lauren.”

I don’t know what became of Andrea. After the program, we lost touch. I know Lauren didn’t publish another book. She got her degree and disappeared into the soft world prepared for her since birth, a world in which Andrea and I would never set foot. And to be honest, I don’t blame Lauren for anything. In the arts, you have to use everything at your disposal, every advantage you can, to do what you’re called to do. If I’d had fancy connections and book deals, I’d have been leveraging those things. Andrea would, too. Without a doubt, there’d be a book of short stories with Taylor Swift’s face on the front and Andrea’s on the back.

But sometimes, when I see the same things over and over, when I see the vampires and shills of the publishing world salivating over the shitty writing of a young, attractive first-book all-star, who—let’s be honest—can’t help that she’s young and attractive or that her writing is shit, I don’t feel all that compassionate. I don’t blame her. I feel angry at the cynicism in the marketing. I know she’s a lost kitten who only wants to be loved. But when I read something like this about to come out with a Big Six publishing house, I might feel inclined to kick her off my front step:

In the little courtyard off Piazza di Santa Maria, the robins are flitting like a crimson rain around the fountain and the statues of great writers no one remembers. The sky is sad, overcast, and the wind from the café carries the scent of patriarchy and the tears of the forgotten whose poems will never be spoken. You sit across from me in the melancholy breeze, sipping your Cinzano, your long lashes seductive and unaware of the robin at your elbow, and I am brought back to the fields of San Salvador. The robins are joyful, but soon they will cry.

I wonder if this person’s parents are famous designers or wealthy investors or successful movie producers. I hope so. Otherwise, the sky will truly be sad after this book gets pushed out to pay some business debt that has nothing to do with its author or its contents.

My smoke breaks with Andrea may have taught me more than the classes we were in. At least I’m still working. I hope Andrea is, too. Now I can look back at our writing program with a certain amusement, maybe amazement. I am not a monster, most days. And I wouldn’t say no to anyone who wants to write a book and happens to have the juice to put that book in front of a large audience. Better this author than an AI; though, an AI might write it better.

In my more generous moods, I want to bless anyone who cares about literary fiction enough to get involved and try to make some. But the Andrea part of me, the skeptical, hard-hearted part, is still standing in the snow, thinking, “What the fuck?”