I have been plagued by anxiety and depression my entire life, since before I had words for it. And recognizing that these are highly idiosyncratic inner states—admitting that there is no general cure or perfect treatment that can always be prescribed for how anxiety and depression can link up with each other in the mind—I feel confident that avoiding medication has mostly been right for me, while it may not be right for others. I choose alternatives like exercise, diet, reading, and worst case, staying in bed and just riding it out.

Still, I have moments when I wonder whether it wouldn’t be preferable to take some heavy mind-flattening chemical that lets me shuffle dimly through my days, sleep soundly every night, and never feel upset or afraid. Because, in the end, every life must come to the same conclusion, whether one chooses to suffer or not. As the saying goes, at the end of the game, the pawn and the king go in the same box. But I don’t suffer constantly from anxiety and depression, only sometimes. And that’s what makes the straight-edge option viable.

The capriciousness of my mind keeps me wondering whether any given day might turn horrible without warning or reason. Living in that uncertainty was, for many years, its own kind of torment. It took me a long time to learn how to flow with my inner states, to recognize the onset of certain nasty, petrifying feelings arising seemingly out of nowhere, and say, well, it looks like today is going to be one of those.

Yesterday was one of those. Maybe today will be, too. Maybe being halfway through Blood Meridian made it worse. It certainly didn’t make anything better. McCarthy’s writing seldom does. It’s not something one reads for pleasure. At least, I don’t.

I read him because I have a certain abstract appreciation for phantasmagoria and beautiful sentences. But it’s not like reading The Sun Also Rises or Never Let Me Go. I never feel close to McCarthy’s characters. He doesn’t let the reader identify or care too much about the people in his books. Instead, there’s a cold distance, a stipulation that the reader detach himself from the narrative and view it through a thick pane of glass. And Blood Meridian seems more essentially this than any of McCarthy’s other writings.

This morning, I found myself on page 178 (of my third reading) of the novel. And I was having problems with it. I closed the book and thought, fuck this, trying to recall whether, in 2003 or 2009, I also said fuck this around page 178. I don’t know. But I do know the tendency to tell the book to go fuck itself gets strong at least once a read-through. I never felt like saying that about The Road or Suttree or All the Pretty Horses or No Country for Old Men. Sure, they had the pane of glass, too. But there’s something about BM that gradually makes me feel as though I’m visiting the novel upon myself instead of merely reading it.

So I resolved to return it to the library. That’s it. Boom. Done. I’ve read the damn thing twice. Shouldn’t that be enough to say I’ve done my due diligence on McCarthy’s magnum opus? It should be enough. I have Maupassant’s complete stories waiting in a dual-language edition and by god . . .

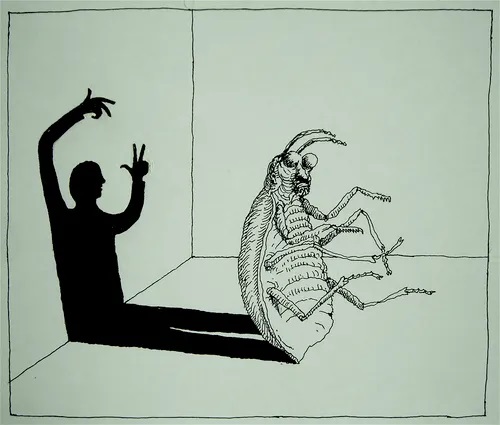

But then I felt worse. As Donald-45 might put it: “So much worse. Sad.” And I started to laugh (actually laugh-cough because I’m at the end of the first month of The Cold I Cannot Kick). The ponderous weight of my unfortunate, Kafka-esque gallows humor reasserted itself. And I saw how much more Gregor Samsa I’ve become over this last year of sickness and dread.

I often feel like the world is knocking me around. Obligation is both the cause and the formula: I find myself obligated to do a certain thing and must therefore tolerate a comparable amount of abuse. Mo obligation, mo abuse. It’s that simple. And I’ve never had more obligations than I do at present. Maybe the reason I find Blood Meridian so hard to swallow is that, not unlike Gregor, I’m constantly taking my medicine (straight-edge option no longer available), constantly being force-fed bad-tasting syrupy obligation after obligation, and asking for more.

If I don’t maintain perfect discipline, if I don’t visit an outsized portion of responsibility upon myself and make sure everyone around me is satisfied and at ease, what then? Unlike the unbending, ruthless, willful characters in Blood Meridian, I might be undergoing a certain metamorphosis. None of them turn into giant cockroaches. Various other beasts and demons, maybe, but not into Gregor Samsa.

I am the giant cockroach of the Family and Consumer Sciences Department, sitting in my dark office at 6:15 AM (the lights go off if I’m too still—I have to remember to wave my arms every five minutes), worrying and ruminating, struggling with this novel, but really with myself, asking, “Where did I go wrong?” Because I most certainly did. And here I am, obligated and tolerant, feelers extended.

One imagines that cockroaches don’t read novels. Or, if they do, that they prefer works in the Tumblr-Tik-Tok genre of “dark academia”—Hogwarts without the magic and with double the soapy intrigue. Dark because cockroaches don’t like light. And academia because, well, have you been to college?

Yes, I feel sorry for myself and I probably shouldn’t. Blame the anxiety or the “evening redness in the West.” I feel kicked around by life. I feel anxious and depressed and inappropriately tolerant in the service of my many pressing obligations. But I also know that, in an hour or two, when someone knocks on my office door with an urgent dilemma that only I can fix, I’ll be courteous, friendly, and prompt. And I’ll smile, hoping they don’t look too closely at my face.

I try not to twitch in my ill-fitting mansuit; though, the metamorphosis seems just about complete. I know this because I will continue visiting Blood Meridian upon myself. I will tolerate the book to the end. Perhaps, instead of Maupassant, I’ll read some Donna Tartt next along with my other hive-mates. But, for now, I can console myself with the thought that if I stay very still when I laugh, it won’t turn on the lights.