One of my favorite Johnny Cash songs is his cover of Porter Wagoner’s “Satisfied Mind.” The refrain goes like this:

How many times have

You heard someone say

If I had his money,

I could do things my way

But little they know

That it’s so hard to find

One rich man in ten

With a satisfied mind.

It’s very country and it rests on the country music genre cliché of human relationships being more valuable than wealth, status, and power. It also makes me think of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Richard Cory,” from Sounds of Silence, which was the first time I encountered the idea in music outside my uncle’s self-produced country albums. Richard Cory has everything, then shoots himself, yet the impoverished speaker in the song continues to envy him. They’re both good songs. They both carry a timeworn message in popular music: money can’t buy love.

Still, as a cynical friend of mine has pointed out more than once, it may be true that money can’t buy love, but it can buy travel, leisure, interesting rich-person adventures (vs. the poor-person variety), politeness, serenity, entertainment, granite countertops, educational opportunities, good food, access to the gifted and fascinating, and quality healthcare, which in the aggregate starts to look a lot like love. Love of the world. Love of life. Love of fate. Amor fati.

It’s easy to love what your life has become when you can do things your way. Oh Allfather Zod, I don’t often pray to you (because why? I have a shit ton of money), but I’m here at your subterranean temple of fire and perdition on Zodsday, just like last year, to recite my only prayer: DON’T CHANGE A THING. Amor fati, you know? I’m good. You do you.

The rest of us will have to sacrifice two blocks of insect-soy protein at the altar of the Allfather on a regular basis or our paranoid, sadistic deity will smite us. We may ask ourselves why the Sam Bankman-Frieds, Martin Shkrelis, and Anna Sorokins of the world have millions (ostensibly there are many, or at least some, of these individuals who have not yet been indicted), while we labor in Zod’s gulag, but that’s asking the wrong question.

The real question is whether we are about to own nothing and be happy, which is to say, whether we are authentically mentally ill (as opposed to performatively “mentally ill” as part of a curated online identity). Think of Elon Musk declaring that he was just going to live with friends for the rest of his life instead of owning houses—because friends are the spice of life, no? I wonder what sort of friends Elon has. Sure, take the fifth wing. Yeah, kitty-corner from the spaceport and the athletic complex. Stay as long as you like!

Amor fati, brother, amor fati.

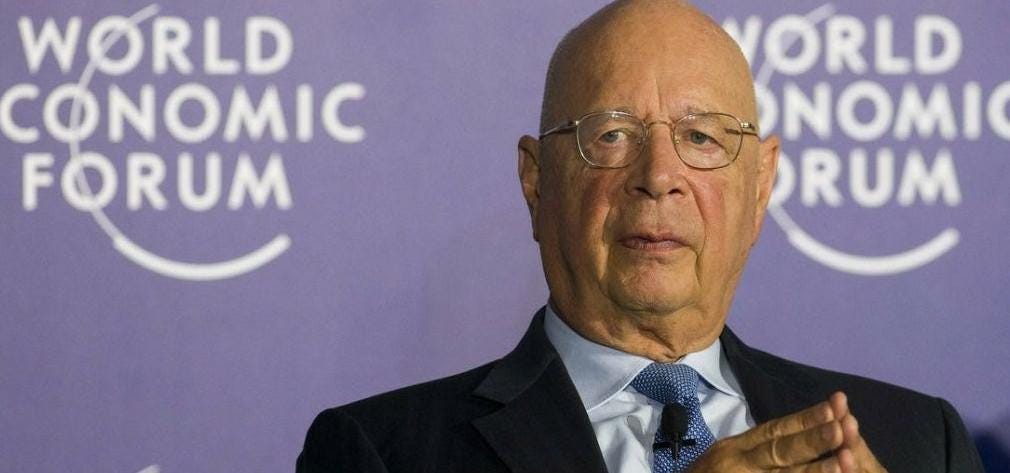

If the definition of mental illness is, to a certain extent, mediated by culture and indicated by transgressions that show deviant behavior (i.e. behavior that indicates deviation from cultural norms), then Elon’s version of owning nothing might qualify. Klaus Schwab’s utopian vision of the post-pandemic “Great Reset,” in which every human culture, corporation, nation, and industry must immediately “act jointly and swiftly to revamp all aspects of our societies and economies, from education to social contracts and working conditions” likely also qualifies.

We might ask why utopian visionaries, who seem to know the truth and have a final solution worked out for the world, always end up as Robespierres. Moreover, why do social movements dedicated to “diversity, equity, and inclusion” tend to devolve into bitter gestures of intolerance, over-compensatory bias, and exclusion? Well, money. It’s the economy, stupid. And pandemic dread really seemed to fuel that sort of white-knuckle utopianism. It goes without saying that any future vision according to a tight group of political and economic experts will not stay very bright.

Utopia nearly always leads to the dys– version. Utopian visions born out of pandemics and other global traumas seem the worst. As the British sci-fi roleplaying game, Carbon 2185, put it: “Carbon 2185 has a highly detailed economy with reference tables and charts to help you instantly know how much a bowl of street ramen costs.” I tried playing this game by post with some friends during the pandemic and we gave up. According to the rules, a bowl of street ramen cost more than my monthly take-home and we had to rent all our guns. I’ll pass on the ramen, thanks. Bring on the insect-soy. It was depressing. Someone proposed D&D instead. Someone said, “Fuck that.” We didn’t talk for a bit.

Why lean into cyberpunk dystopia when talking about the future? Why put a frame of Max, from Elysium, visiting his parole-officer bot, who asks, “Are you being sarcastic and / or abusive?” at the top of this piece? Why call it, “Digging to China”? Am I implying that, in the Monbiot-Thunbergian horseshoe irony of the post-pandemic near future, we will be eating processed insects and living in the pods of a grubby rental economy, where the CCP and the USA have arrived at the same socio-economic terminal? Am I now going to start referencing the episodes of Black Mirror that made me the most depressed because they seemed the most likely? Am I committing tone crimes and microaggressions in this paragraph? I’ll spare you.

Instead, I’ll propose that there has never been a better time to stop monetizing your hobbies (or your art or your body). The impetus for such a proposition comes from Colleen Doran’s excellent, “How Long Does it Take to Draw a Comic Book Page?” on Colleen Doran’s Funny Business. I love Colleen Doran’s newsletter. She’s a wise professional who’s been around long enough in her industry to have a few things to say about creativity, money, and staying sane.

At the same time, the way she tracks her time (“I tried to stick to an eight hour day for awhile, but it is impossible for a working cartoonist to work only 8 hours per day.”) reminded me of how I’ve been tracking my fiction words-per-day and how stressed I’ve felt (for decades) about staying productive. Where does this stress come from? From the same economic imagination that envisions being priced out of a bowl of street ramen. From illusions like “upskilling” which seems to borrow logic from the old trickle-down economics that clearly worked so well. And the self-publishing option is no consolation for a working writer. You have to grind. You have to write more or nothing works. You have to monetize everything and keep a straight face. No sarcasm permitted.

Yes, there have been some slot-machine winners in the self-publishing game (read their work and the slot-machine metaphor will begin to make a lot of sense). There have also been slot-machine winners in social media influencing, self-managed parasocial porn sites, and various forms of crowdfunding. And I have no doubt that some of it is good (Chuck Wendig’s writing comes to mind along with the band, Scary Pockets—no comment on OnlyFans and its clones). But mostly people seem to have been lured, at least for a while, into another self-exploitation gulag.

The self-publishing platform (Amazon, Lulu, etc.) now stands in the place of a traditional publisher, only with non-existent gatekeeping. Sure, buddy, you’re an author now. Good luck with that . . . another utopian vision gone westward to seek its fortune while the company takes its cut.

As a writer, you will eventually eat the bugs. You will own nothing. You will labor to pay rents to monolithic inhuman organizations with AI customer service—economic entities that conflate sarcasm with abuse and practice zero tolerance toward any microaggression that may question their mission statements. You will prostitute yourself from your temporary pod. And you will be happy.

I’ve learned a lot about how my body and mind get monetized by scrupulously tracking time spent working on various projects. I think Colleen Doran and my many creative friends are right to pay attention to how they’re spending their days. But I also think, absent a trust fund, time and grind eventually converge violently in you. The personal sacrifices, the mental illnesses, the continual self-betrayals in the interests of time, money, and productivity point more to the cruel altar of Allfather Zod than to some glorious worker’s paradise.

Consider this hypothetical. You’re standing in your kitchen, cutting slices of cheese with a razor-sharp carving knife. You realize there are such things as cheese knives, but you don’t have one. For those readers currently languishing in suburban opulence, who can’t imagine someone not owning a cheese knife, I’m here to tell you such people exist, and they are probably more numerous than you have imagined.

Consider this hypothetical. You’re standing in your kitchen, cutting slices of cheese with a razor-sharp carving knife. You realize there are such things as cheese knives, but you don’t have one. For those readers currently languishing in suburban opulence, who can’t imagine someone not owning a cheese knife, I’m here to tell you such people exist, and they are probably more numerous than you have imagined.

Reeling this morning from my all-Trump-all-the-time ulcer-inducing news feed of despair, I closed my eyes and focused on my breathing. I’ve been a compulsive news reader since I learned how. And, for the last few months, my morning habit has evolved into a kind of shamanic pathworking. Not the startup-bro takes ayahuasca at Burning Man to dream up new apps sort of thing. More like: I drank the cobra venom and I might be having an aneurysm but, if I live, I’ll probably learn something. Because that’s why we read the news, right? To learn something?

Reeling this morning from my all-Trump-all-the-time ulcer-inducing news feed of despair, I closed my eyes and focused on my breathing. I’ve been a compulsive news reader since I learned how. And, for the last few months, my morning habit has evolved into a kind of shamanic pathworking. Not the startup-bro takes ayahuasca at Burning Man to dream up new apps sort of thing. More like: I drank the cobra venom and I might be having an aneurysm but, if I live, I’ll probably learn something. Because that’s why we read the news, right? To learn something?

things about rain: schließlich, regnet es auf der Wiese. Or something like that. Maybe that’s all I need.

things about rain: schließlich, regnet es auf der Wiese. Or something like that. Maybe that’s all I need. the town fathers for leading a black mass in the woods, I’m close to just dosing up, crawling back into bed, and moaning myself to sleep.

the town fathers for leading a black mass in the woods, I’m close to just dosing up, crawling back into bed, and moaning myself to sleep.

later, the obvious part seems far more dominant than whatever might have proven insightful. It’s 2016. Has the sheer science-fiction-horror-dread of this moment in time caught up to us from the back end of the 20th century yet? The future is not evenly distributed, at least the good parts where someone like me can get bionic knees. In 1982, Blade Runner gave the world a vision of rebirth after decay instead of the unadulterated Kali Yuga we’re entering now.

later, the obvious part seems far more dominant than whatever might have proven insightful. It’s 2016. Has the sheer science-fiction-horror-dread of this moment in time caught up to us from the back end of the 20th century yet? The future is not evenly distributed, at least the good parts where someone like me can get bionic knees. In 1982, Blade Runner gave the world a vision of rebirth after decay instead of the unadulterated Kali Yuga we’re entering now.