Write seriously for any length of time and you learn that it’s a lonely business. Whether you’re writing essays, stories, poems, scripts, or novels, it’s just you and the page every day with no guarantee that your enormous investment of time, emotion, and energy is ever going to reach a satisfying conclusion. As Charles Bukowski wrote, you’re “betting on the muse.” And the muse is a cruel mistress.

Even if she’s the love of your life, sometimes you find yourself wishing the two of you had never met. Maybe, you think, if I hadn’t gotten addicted to writing, I might have made real progress in a day job. I might even have reached a point where I could have moved out of my tiny apartment, started paying off my student loans, and bought a car less than 30 years old, a respectable adult at last.

Instead, I chose to take all that energy and put it into words. When I’m lucky, when the muse deals me a good hand and I play it for all it’s worth, the words seem like they’ll never stop. There’s no better feeling than that. But no one can be lucky all the time. And sometimes you just go bust.

It doesn’t matter whether writing is a hobby or the way you keep the lights on. All writers have to face the same ups and downs, the same uncertainties, the same droughts, the same bad runs, the same unforgiving emptiness of a blank page with the muse nowhere to be found. Even the most talented among us can feel like imposters when we bet it all on one hand, fold, and leave the table with nothing but pocket lint and remorse.

But now we’re in a new abnormal. There’s a virus and civil unrest in the streets. Everything’s shuttered or broken. And our homes have become sci-fi biodomes where we drift through the day in a weird online approximation of the lives we used to lead. Lockdowns do that. Pandemics can change everything, even our writing habits.

Attending a poetry reading or just walking through a bookstore can feel like playing chess with the reaper. Surgical gear is the new black. And we can’t waste time in a coffee shop anymore, glowering at a blank screen over a latte with enough sugar to induce an intracranial coma in an elephant. That was the old world, old rules, old normal. Now everyone’s socially distanced and weird. Now everyone’s living like a writer.

We wait for life to reacquire some semblance of normalcy. We grieve for those who’ve died and want to safeguard the lives of those who haven’t. We keep in mind that all life is precious and that we’re in this together. And we hope that those who are now unemployed or alone or going into debt because of COVID-19 can find a way forward. We hope this for ourselves, too.

Yet, as with any pandemic, riot, or plague, there are darkly amusing dimensions. As a friend of mine put it recently, “This can’t go on for much longer. It’s just too stupid.” I had to agree. It is. Then again, he’s not used to betting on the muse, to leading a solitary hidden life with no assurance that the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t just an oncoming train. Writers are especially poised to continue work through a pandemic.

State Dependency Writing Works in a Lockdown

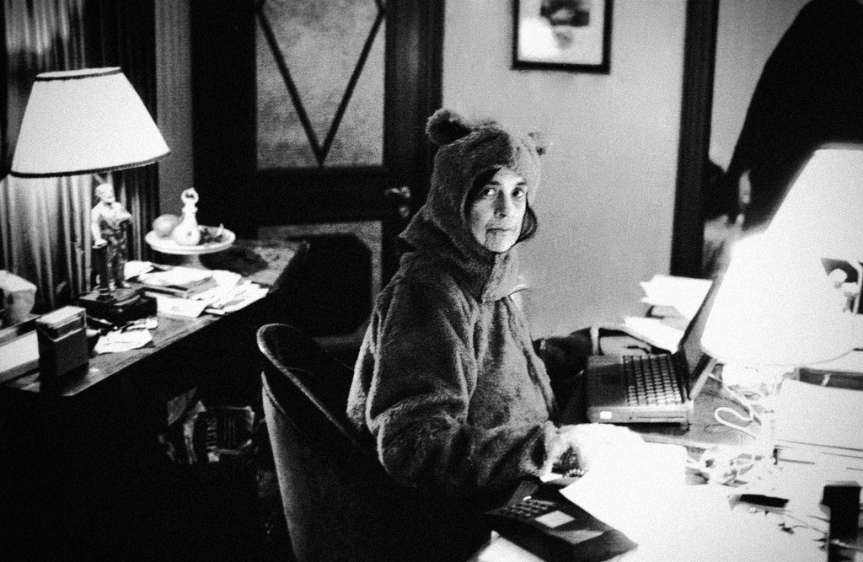

Ever wonder why you can’t seem to get into a good flow state without your bagel and cup of coffee? Why the little rituals and routines of settling down to write seem so essential? When you look at them rationally, they’re really nothing—small mundane comforts, little observances in your personal space, that pink bathrobe with the embroidered toucan on the back you only wear when you write.

Was it grandma’s? Did you get it at a yard sale in 1993? Or was it always waiting for you up there in the attic, waiting to become the key element that helped you finish your first novel manuscript? You don’t want to think about it. It’s your magic writing bathrobe. If you look at it too closely, the magic might go away.

I understand. I’m not here to gainsay your magic. But I will suggest that memory and brain chemistry are part of it. And this is why it still works when the rest of the world is stuck at home, day drinking and fantasizing about haircuts. Therapist and licensed counselor, David Joel Miller, calls it “environmental context-dependent memory” or “situational memory.” And it’s probably why I’ll be acknowledging Krispy Kreme when my third story collection gets taken.

Miller explains it as “an ability to remember information in one situation that you are unable to remember in another.” It’s closely related to state-dependent memory, which has more to do with internal chemistry than with location. Generally, we can say that both types of “state dependency” are invoked by our little magical writing habits.

Are We Talking About Trance States?

Yes and no. If “trance” is defined broadly as an altered mental state, then yes. We go into trances all the time—driving our kids to school, washing the dishes, binging five seasons of a show we can barely remember a few days later. When we do anything familiar enough that it becomes rote, we’re probably doing it in a light trance state.

This is not inducing a David Lynchian out-of-body dissociative episode where we have a conversation with a dead prophet on top of an Aztec pyramid and realize the existential meaning of our lives. We’re awake. We’re functional. We’re just in the flow state that Mihaly Csikszentmihaly, the founder of Positive Psychology, describes as a period of total absorption.

He calls flow “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.” That sounds like my compulsive writing habit, my ongoing love affair with the muse. I also know that, when she deals me a bum hand, flow is impossible.

So just as a gambler will blow on the dice, keep a lucky talisman in a vest pocket, or say a quick prayer to Our Lady of the Full House, we fire up a triple espresso and get a chocolate iced glazed donut. We creep up to the attic and put on our toucan bathrobe. Because these invoke our situational memory of having written, of being in that enjoyable flow state.

Speaking of the Devil

Legendary writer and Iowa Writers Workshop professor, Madison Smartt Bell, recommends everything from post-hypnotic suggestion to binaural beats. In a 2011 New Yorker interview about his novel, The Color of Night, he notes that “Normally most writers don’t say, ‘I’m going into a mild hypnotic trance.’ Typically they don’t know how they do it. . . . Most people, when they have a good experience writing, they’re well placed in that state, which is also sometimes called a ‘flow state.’ If you don’t have trouble, you don’t have to think about it. But if for some reason you can’t get into that state, then you start to have writer’s block.”

Most of my pragmatic fiction writing teachers didn’t like to talk about writer’s block. Often, they denied its existence completely. I think it was because they were superstitious. Speak of the devil and he might appear. The most instruction I ever got along these lines was in the last year of my MFA, when the leader of our advanced fiction workshop said: “Your job as a writer is to go into a trance such that, when you come out of it, there are words on the page.”

So here we are in this afraid new locked down world with non-writers drinking wine in our attic and sad news on television. In times like this, writing is as essential as any form of art. And we’re the ones to do it.

We simply have to remember that even though the muse is fickle, even though sometimes we’ll hit a bad run, we can improve our odds by sticking to our rituals. When we can forget what’s going on in the outside world and enter flow, we won’t be writing in spite of the lockdown. We’ll just be writing. And that’s a wonderful place to be.