Black Swan is Midsommar. Stop talking, Winston.

Hollywood has never seemed more Orwellian in its insistence that it is the repository of everything admirable in culture and that it represents the right side of history. We know Hollywood will hold its own mother down and pull the gold out of her teeth with a pliers, but it prefers to pretend otherwise. And no one wants to dwell on this as long as the entertainment keeps coming. With streaming, the rapaciousness of the entertainment center of the world is even harder to see. Hollywood says it’s your friend. In reality, it’s INGSOC conformity and you’re awful if you disagree.

Streaming technology is as 1984 as it gets.

The tragedy of streaming content is that it never goes away. It’s in your house, up in your perceptual field, at all times. Even when you’re not watching, you’re getting emails reminding you to log back in. Back in the halcyon days of Blockbuster Video, a pretentious, emotionally manipulative stinker might show up on VHS, but there was a bit more personal agency involved in renting and watching it. It wasn’t accessible unless you physically sought it out. It was a tangible thing and you weren’t quite such a passive blob of content consumption—seeing the movie demanded that you get up, at least temporarily, from the couch.

You also didn’t have the same plausible deniability if you found yourself watching a lousy film. At some point, from the rental store to the final credits (if you made it that far), you had to remind yourself that you put down good money for the thing and brought it home. You did it to yourself, friend.

In the worst cases (Tree of Life? Vanilla Sky? The English Patient? Legends of the Fall? Crash? Life as a House?), you may have admitted that you were powerless against the overwhelming pretentious hype-suction and were thereafter drawn into a vortex of melodrama against your will. Then you may have made a searching and fearless moral inventory and resolved never to relapse again. Sometimes, bringing back drippy garbage from Blockbuster could be a cathartic, healing experience, like going out with the guys while on Antabuse. The best lessons are the ones we teach ourselves.

But now, with streaming television and movies, everybody’s on the juice 24/7 and done learning. You can now quietly demean yourself with bullshit Hollywood affectation and faux-political posturing every month for a discreet subscription fee. Nobody has to know. You don’t have to look the Blockbuster cashier in the eye and say, yes, I want to rent The Fountain. You can violate yourself, from beginning to end, with all the pungent streams you desire in the privacy of your home. Draw the curtains. Click on I Am Love. It’s okay.

You might occasionally feel a twinge of self-criticism—why have I watched Babel 15 times and The Maltese Falcon only twice? What does this say about me? But there are certain politically coded stinkers that remain beyond criticism, no matter how fetid and endless their streams may be. Those are the films you are permitted to enjoy without needing to painfully reflect on why you are doing it to yourself. Or if you do happen to wonder, the Party has provided a simple thought-stopping idea: because I am a good person.

The Party tells me I enjoy Magnolia for its drawn out emotional exploration of human meaning and compassion in the San Fernando Valley, a concept which, in itself, is astounding. Thankfully, it’s streaming right now on Netflix. I watch Magnolia because I am good. It provides an emotional release and ultimately represents the best parts of me. I enjoy what is good because I am a good person. War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength. Thank you, Netflix. I feel happy. Let’s watch it again.

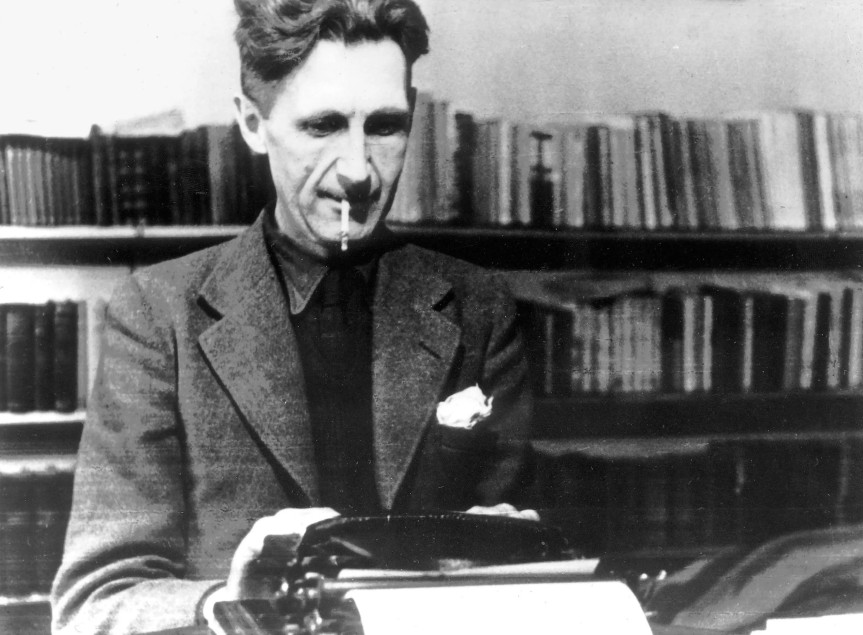

What’s going on in my brain? Why is George Orwell haunting my laptop?

Ideally, a movie will go through a production funnel that starts with a compelling idea, and ends with a completed feature. Along the way, there will be setbacks and workarounds, windfalls and compromises. And as Rachel Ziegler, the most likeable actress in Hollywood, has so famously put it, “That’s Hollywood, baby.” * But we do not live in an ideal world, which means the “completed feature” can come into being before its concept. That, too, is Hollywood, baby. In fact, that’s even more Hollywood than Hollywood. **

A film is sometimes made and then the hype apparatus around it tries to make it into something. Is it a trenchant commentary on the state of race relations in inner-city schools? It could be. Is it a masterwork of ironic feminist critique? It could be. Is it a moving historical epic in which unrequited love is cast against a tapestry of chaos and war? It could be. Let’s see. And if we can’t “position” it—

A book publicist once asked me how I’d position my second short story collection, Cruel Stars. I said, “Wut?” She took a deep breath and said, “What are the books on either side of it in the bookstore?” Then I took a deep breath and said, “Well, the one of the left is, of course, my first collection, Gravity. The one on the right is the collection I’m just finishing, Living the Dream.” She nodded slowly at something over my shoulder.

—does it even exist? Art is nothing without the marketing because marketing is what communicates The Message, the values of the Party. It explains why you are good, why certain things should make you feel happy and sad, and why this should matter to modern audiences. And if such an explanation is impossible or requires too much scaffolding, the Party might want to delay the release or even consign it forever to the vault.

But those of us who are not Party members, who are not on board with what passes for the New York Times concept of the right side of history, may object that this seems untoward for everyone concerned—like pushing a baby back in so the birth might be restarted more strategically, in a more profitable and impactful time.

Most unfortunate. When something is created, you can’t uncreate it so it can hit the zeitgeist more advantageously. You can only change it. And generally the more post-hoc changes and delays you make to a creative product, the more it becomes a horrific golem, an accidental parody of a commercial concept, instead of a coherent piece of art. Put differently, one usually does not do a thing and then justify or position it without making a mess. No, no, I’m not criticizing the Party. Don’t look at me like that. I’m merely making a small, harmless observation . . .

This brings us to the example of Black Swan and Midsommar, which is the same horrendously pretentious, emotionally coercive movie.

Black Swan is now available again on Netflix. We might say it’s been raised from the dead one more time thanks to the always-already necromancy of streaming video. It’s definitely a film approved of by the Party: a break-up story, masquerading as feminist folk horror, in which the main character, Nina, is romantically involved with herself and finally decides it’s not working out.

There are certain inchoate feelings loudly expressed. There is a certain amount of weeping and there are various episodes of emotional violence that we are encouraged to think must mean something. Sympathizing with her struggle (even if she would seem repellent and self-involved to non-Party members) means you are good. You get the message. You are indeed on the right side of history.

Midsommar is the same break-up story, masquerading as feminist folk horror, in which the main character is also romantically involved with herself and finally decides it’s not working out. Sympathizing with her struggle (even if she would seem repellent and self-involved to non-Party members) also means you are good. Criticizing this Frankenstein’s monster of highly telegraphed political position statements means you are a counter-revolutionary, a subversive, not of the Party. You are bad.

To be fair, there are some hapless men who travel through the scenes of these movies like runaway spaceships soon disappearing beyond the rings of Saturn, behaving awful or squeamish or unreliable according to the plot-furniture needs of the moment. At least one of them is immolated in a bear suit, which might be interesting if we could bring ourselves to give two shits about him. Instead, we think, well, there he goes. He’s a crispy critter now, kids. Woo.

The reason Black Swan-Midsommar is a good example of Hollywood’s shallow, monosyllabic politics is that these films (or we might say, this film) are actually very overt in their need to seem right and to make you agree that they are. They’re the same yoked-up melodrama we’ve always gotten only now repositioned as edgy and essential, now back in our homes, telling us about politics and social justice, and not going anywhere.

They’re pretending to be one thing (folk horror) as a container for another thing (third-wave feminist critique) and are actually neither. They’re telling us that if we like this, if we watch it many times, if we digest it, if we approve of it, we “get it.” We’re in the know. We’re correct. And so we are good human beings. 2 + 2 = 5. Of course, this is abject bullshit.

Why is Florence Pugh having a hysterical meltdown throughout the movie? Stop talking, Winston. It doesn’t need to make sense. Just go with it and you’ll be safe. There is no need to think critically or make small, troubling observations. All you need to do is accept that she is sad. You may cry with her if you wish. That shows solidarity and that you are loyal. Yes, you are a true believer . . .

Unintentional Orwellian patterns are ubiquitous, especially in the pop-culture mediated by Hollywood, which is most pop-culture. Orwell wasn’t just concerned about totalitarian communism, his deeper project was criticizing thoughtless social conformity in general.

For example, in Keep the Aspidistra Flying, one of his largely forgotten novels (perhaps because it cuts a little too close to middle-class status anxiety and the obsession with money), the protagonist, Gordon Comstock, gives up on art to make a modest living in advertising. What is art without marketing, the novel asks? In the end, when he discards his poems, Comstock concludes it really is nothing.

Ultimately, there is no accounting for taste. There is also no accounting for technology. And when taste and technology coincide, there is no accounting at all. Black Swan and Midsommar would have flashed through the pan with a lot less “positioning” had the big streamers not put them in perpetual rotation—unlike many far superior and less ideological films, which blink out of existence on streaming platforms all the time.

We hope Hollywood goes on a retreat in the mountains and finds itself, comes to terms with its pathological need to always be class president, and decides to stop bullying its audiences. But the aspidistra’s airborne and, let’s be honest, nobody knows how to land.

—

* Interestingly, it’s the same when writing a novel, only you get to create all your own obstacles, betray yourself, meddle with your own story, make all the compromises, and know from the beginning that you’re not going to get paid.

** There is no point in arguing that a particular production “isn’t mainstream” or isn’t influenced by Hollywood in whole or in part. The global movie industry in general and streaming technology in particular has had an enormous centralizing effect on film. “Indie” is now a flavor. It is not a substantial alternative.